A Summary of the Srimad Bhagavatham : Ch-5. Part-12.

.jpg)

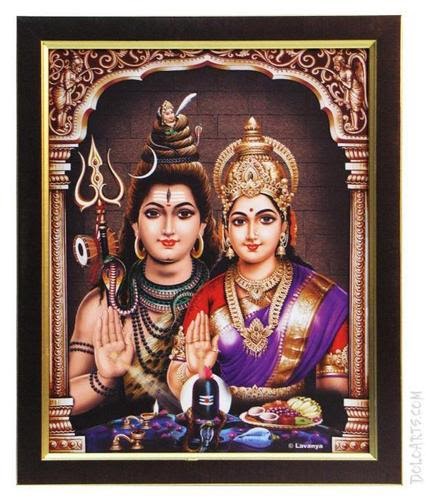

5: Narada Instructs Yudhisthira on Ashrama Dharma : Part-12. In order to go on with this meditation, we have to take our ishta devata for our contemplation. Our ishta devata can be Rama, Krishna, Devi, Bhagavati, Narayana, Siva, Ganesha or whatever the case may be, or if we belong to another religious faith it may be the concept of Allah, Jesus Christ, Father in heaven, etc. Whatever it be, that concept has to be internalised for the purpose of upasana. We should think only that and nothing else, and believe in the protection that it can grant us. The ishta devata protects us, guides us, and enlightens us. It gives us security, and we feel happy with it. Some devotees hug the image of their ishta devata, wear it around their necks, kiss it, and feel that it is their beloved. It is truly that, because it symbolises the divinity that is pervading everywhere. Such kind of upasanas, to mention briefly, are the duties of a Vanaprastha. But there is a still higher stage, calle

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)